3/5 Building Social Capital At Home - FIVE PROBLEMS

Family affordability has been impacted by five problems:

1. Rising costs relative to income

2. Outdated workplace policies

3. Inadequate and poorly targeted government investment

4. People are having fewer children

5. Parents are increasingly isolated

1. RISING COSTS RELATIVE TO INCOME

More Hispanic children are living in poverty—4.2 million in 2020—than children of any other racial or ethnic group.

Let’s begin with the good news: The child poverty rate has fallen considerably in recent decades, from 28 percent in 1967 to an all-time low of 14.4 percent in 2019 (bumping up to 17 percent in 2022).13 Additionally, average income has risen across income quintiles over the last forty years, and taxes and transfers have boosted income significantly for low- and moderate-income households. Yet stopping here would miss economic challenges many families are facing and the ways that affordability could be improved.

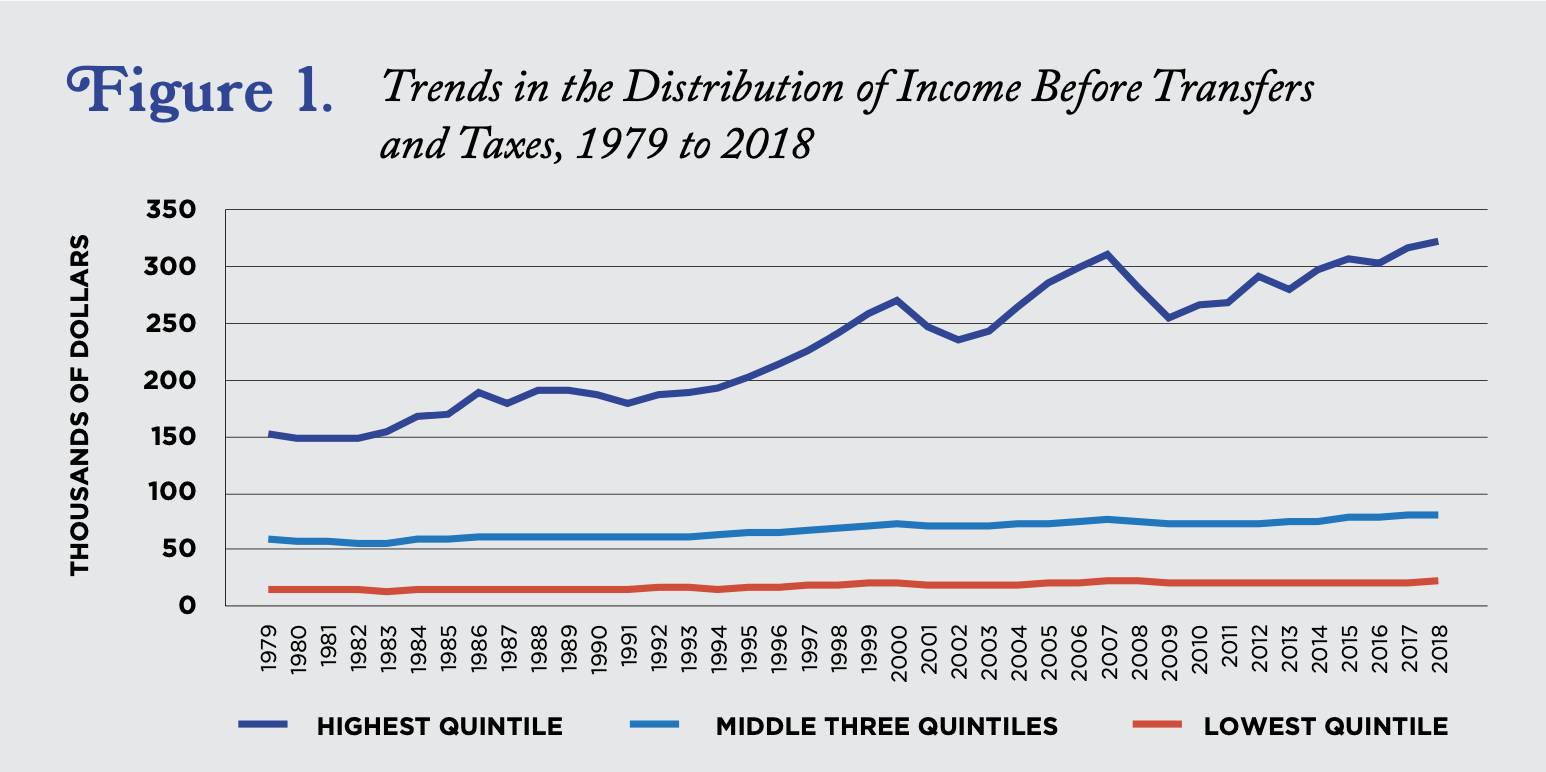

Consider that while average household income increased across nearly every quintile over the last four decades, it grew the least for low-income households.14 Average income before transfers and taxes grew by a cumulative 40 percent among households in the lowest quintile, but that large sounding percentage is in part because the baseline is so low. Real average income grew from $16,100 in 1979 to $22,500 in 2018, or at an average annual rate of 0.9 percent. To be sure, taxes and transfers increased this considerably for the lowest quintile. But as discussed in later sections, Hispanics tend to have a lower take-up rate of benefits relative to other groups.

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

Meanwhile, family-related expenses have risen.

Housing

Consider housing, typically families’ largest expense. The median sale price of a home hit a record high in 2022 even when adjusting for inflation. This creates value for existing homeowners but freezes out those who would like to become homeowners.The rental market has been even worse. The American Community Survey shows that renters

are almost twice as likely to spend 30 percent or more of their income on housing as homeowners are. Housing affordability pressures have increased most acutely in the last decade for low- and moderate-income renters. According to a recent poll from the Bipartisan Policy Center, half of respondents (50 percent) said it has been somewhat or very difficult to pay rent over the past year—with Hispanic respondents (59 percent) and Black respondents (57 percent) reporting greater burdens than White respondents (45 percent). Importantly, the rise in housing costs has occurred in nearly all metro areas, suggesting that escaping these pressures is not easy to do.

Government may be to blame: State and local zoning and land-use regulations— often justified for aesthetic and environmental reasons—negatively impact housing affordability, which in turn impacts family budgets, work opportunities, racial and economic segregation, commuting times (time away from family and work, and increasing pollution), and even children’s educational outcomes.

Education

To the latter point, our public school system, wherein school access is tied to zip code, exacerbates the crisis in housing affordability and expands it to education. According to a recent study, homes are nearly two-and-a-half times more expensive near high- scoring schools as mortgages have become “tuition” for public schools. This puts high- performing public schools out of reach of low- and moderate-income families, who are the least likely to have the financial margin to afford private school. Charter schools and school choice can help alleviate some of these pressures, and Hispanics make up the largest share of students in public charter schools.

Child care

In addition to housing and education, child care is often a large expense for many working families. According to the St. Louis Federal Reserve, child care costs are an estimated 14 percent of median household income, and the expense of child care has been rising much faster than overall prices as measured by the consumer price index. On average, poor families spend a larger share of their income on child care. High child care costs can serve as a barrier to women’s employment as well as result in children in subpar child care settings, the effect of which can have lifetime ramifications.

SOURCE: Department of Agriculture.

Again, government policy may be contributing to the shortage of providers and rising costs. Overly burdensome regulations can drive up costs and prevent otherwise qualified care providers from entering the market, especially smaller care providers—such as family and friend providers, faith-providers, and in-home child care providers—that don’t have the infrastructure to navigate a complicated regulatory environment. Requirements like having child care workers have a Bachelors’ degree, as implemented in Washington D.C. and proposed in President Biden’s “Build Back Better” framework, further drive-up costs for parents and create barriers to entering the profession with unclear impacts on quality.

U.S. average for the younger child in middle-income, married-couple families with two children. Child care and education expenses only for families with expense.

Healthcare

Healthcare is yet another expense for working families. While the majority of Whites receive healthcare through their employers (66 percent), only a minority of Hispanics (41 percent) and Blacks do (46 percent). The uninsured rate among Hispanics is nearly double that of Whites. Given the complexity of healthcare reform, and the smaller relative size of the healthcare burden on families relative to housing and child care, a solution set for healthcare will not be addressed in this paper, though it is important. Behind child care, healthcare represents the largest change in expense for working families in recent decades.

SOURCE: Pew Research Center analysis of 2019 U.S. Census Bureau income and poverty data.

These costs add up to a big bite out of many families’ paychecks. According to the Department of Agriculture, the expenses associated with raising a child from birth to age 17 were around $200,000 for low- and moderate-income families in 2015. Importantly, this is 16 percent higher in real terms than raising a child in 1960, when the Department of Agriculture began tracking expenses, largely due to the increase in child care, education, and healthcare costs. When accounting for inflation, the costs of raising a child today are closer to $300,000 per child.

Families are feeling the squeeze: Nearly half (46 percent) report difficulty paying for personal expenses in the past 12 months compared to 35 percent of non-parents, according to recent polling. The majority of parents (55 percent) say they are “getting by, but do not have the life [they] want,” and an additional 20 percent are “struggling and worried for the future.” Hispanics represent the largest share of children and are also for whom economic insecurity is the highest.

2. OUTDATED WORKPLACE POLICIES

Hispanics have a higher labor force participation rate than average, but the least access to paid leave, flexible work schedules, and remote work options from their employers.

Work is the primary lever of financial independence, and the majority of parents of young children are in the labor force. Yet relatively few workplaces are conducive to this reality, putting financial pressure and stress on American families.

Paid parental leave

This is perhaps best seen with respect to paid parental leave. Only one in four workers had access to paid family leave in 2021, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and nearly 40 percent of workers lack job protection. Among low-wage workers, access to paid leave policies is minimal, with only 12 percent of workers in the lowest wage quartile having access to paid family leave of any duration from their employers. Hispanics have the least access of any racial or ethnic group to paid leave.

Without access to paid leave, many low-income parents go on welfare or take on debt following the birth of a child. A survey by Pew Research reported that households with under $30,000 in income didn’t receive full pay during parental leave: 57 percent took on debt and nearly half went on public assistance. Others hasten their return to work, risking their well-being: one in four mothers returns to work within two weeks of giving birth, according to an Abt Associates survey.

SOURCE: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Flexible work

Challenges with family-friendly workplace expectations continue as children age. According to polls, the number one request that working parents have for employers is flexibility. Yet low- and moderate-income parents often face low wages, lack advance scheduling, inflexible workplaces that prevent parents from work arrangements that they prefer when their children are young. Evidence shows that Hispanic workers have tended to have the least access to flexible work schedules and remote work options.

SOURCE: Glynn, Sarah Jane and Farrell, Jane analysis of the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ American Time Use Survey, 2012.

Lack of family-friendly policies impacts children. In her book What Children Need Columbia economist Jane Waldfogel provides a review of academic literature on child development. She finds that a parent—and most research is centered around the mother—actively present during the first year of a child’s life is crucial for a baby’s healthy development. Yet lack of paid family leave and flexible workplaces limit the ability of parents to spend time with their young children. It’s not just mothers; fathers report spending less time with their children than they would prefer.

Mental health

Work-life balance impacts parents’ mental health.

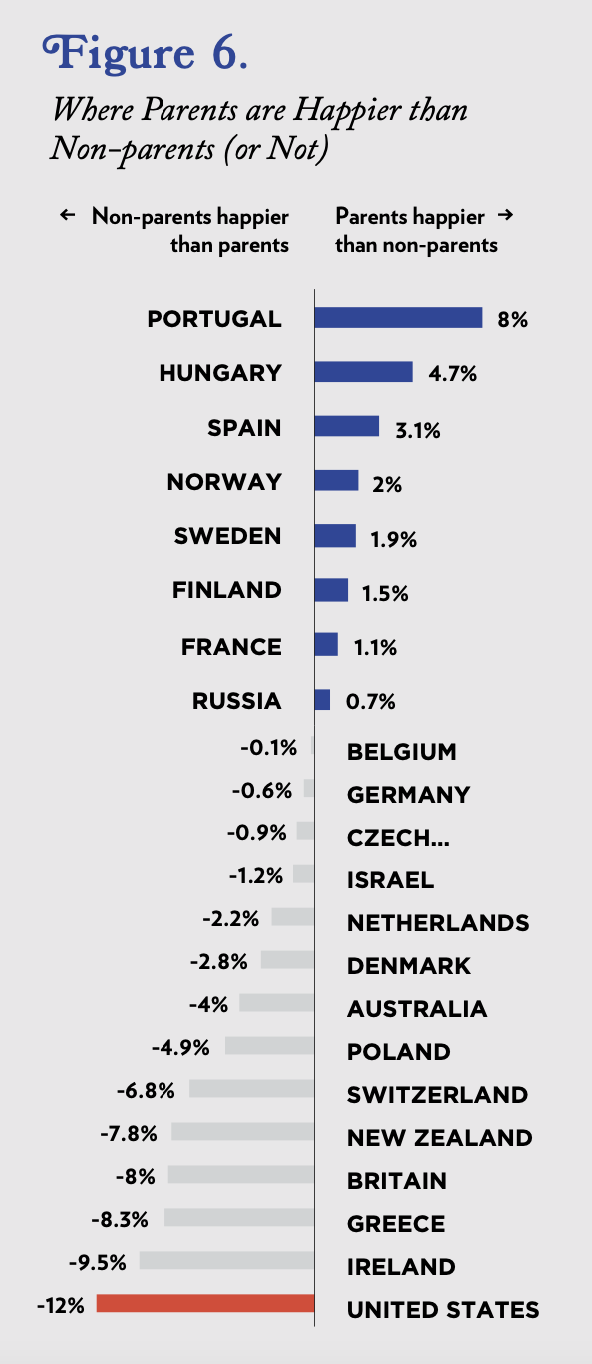

SOURCE: Parenthood and Happiness: Effects of Work-Family Reconciliation Policies in 22 OECD Countries (Glass, Simon and Anderson) Washington Post.

Happy people are more likely to become parents, and more recent studies have found that marriage and parenthood in the U.S. are associated with higher levels of happiness and well-being in the long-run. But work and costs of childrearing appear large correlates to parental happiness in particular.48 For example, a recent study by Francesca Luppi of Bocconi University found that parents who report a positive work-life balance are more likely to have a second child.

Stay at home mothers and female labor force participation

Lack of flexible workplaces and child care has macroeconomic implications by holding back labor force participation. According to Francine D. Blau and Lawrence M. Kahn, about 28 percent of the decline in female labor force participation in America relative to other countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) can be explained by the nation’s lack of family-friendly workplace policies, including paid parental leave and child care. According to a 2016 Gallup report, “Women in America and a Life Well-Lived,” stay-at- home mothers might consider returning to work if the workplace was more accommodating. When asked, 53 percent of stay-at-home mothers say flexible hours or work schedules are a “major factor” in their ability to take a job—surpassing pay and child care.

To be sure, not all parents want to work outside the home in paid employment. About one in five moms and dads in the U.S. are stay at home parents, and a significant share of parents report having the ideal of one parent staying home full-time. Importantly, Hispanic mothers are the most likely to be stay-at-home parents relative to other racial or ethnic groups. According to Pew, 38 percent of Hispanic mothers were stay-at-home moms relative to the U.S. average of 29 percent. This is likely due to a wide variety of factors, including a lack of access to flexible options conducive to family life as previously discussed, elevated marriage rates, and immigration.

According to Pew Research, in 2012, 40 percent of immigrant mothers were stay-at-home mothers, compared with 26 percent of U.S.-born mothers. But it’s also likely reflective of culture and family values. A recent poll found that Hispanics were the least likely group to say that full-time paid child care is the best arrangement for young children. As a corollary, among the different types of child care, Hispanics most preferred relative-provided care over center-based options.

3. INADEQUATE AND POORLY TARGETED GOVERNMENT INVESTMENT

Hispanic families have a lower uptake of government benefits than any other racial or ethnic group, despite their eligibility.

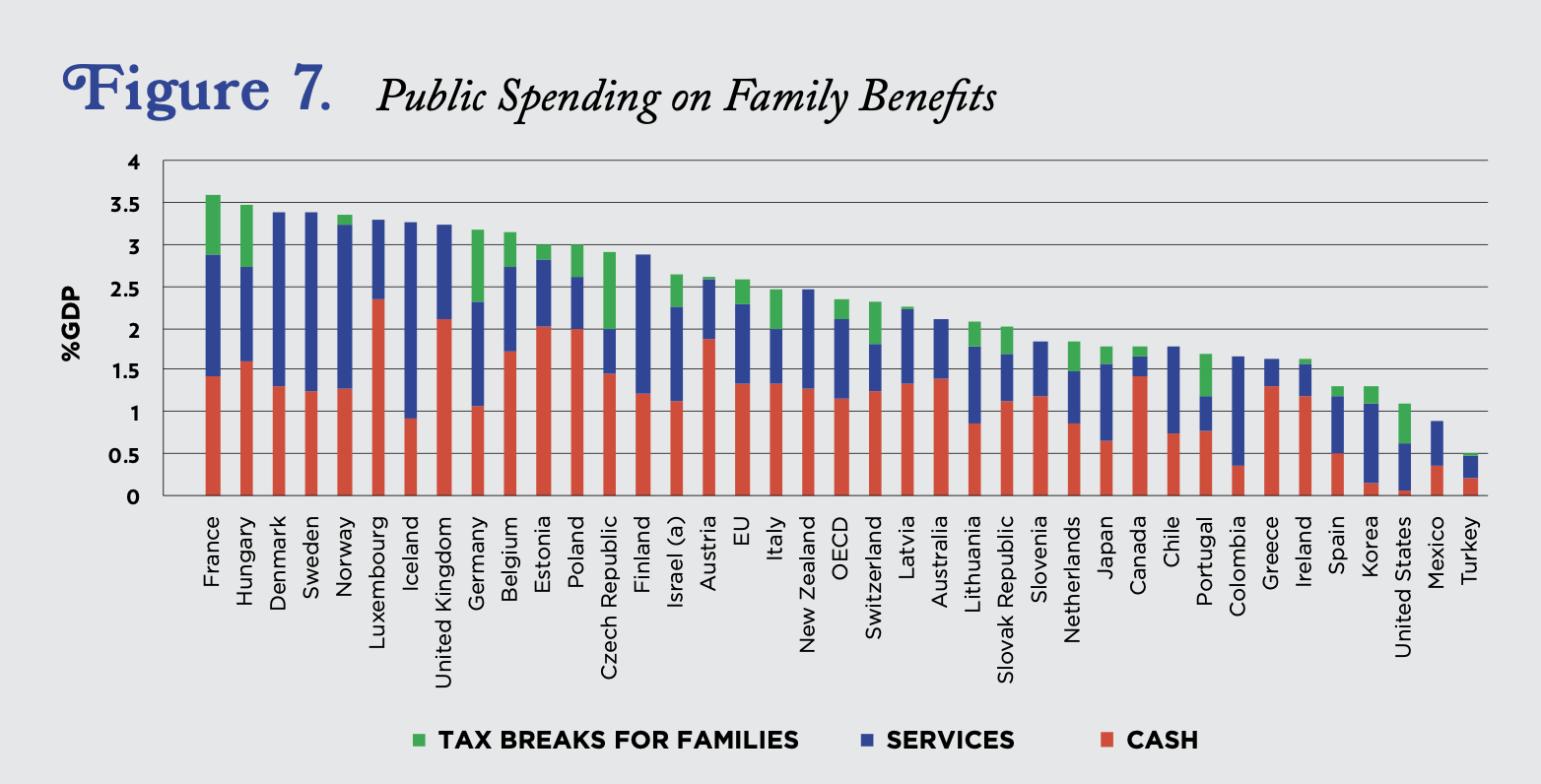

Federal investment in families with young children is a relatively small and declining share of the budget as the population ages. According to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, less than a tenth of federal spending in 2016 was devoted to children, while more than a third was spent on the elderly. Share of spending on families in the U.S. (inclusive of cash support, child care assistance, paid family leave, and other types of assistance) is the smallest of any developed nation except Mexico and Turkey. Cash support given to families is the least of any developed nation.

SOURCE: OECD Family Database.

The system of government programs that does exist is an outdated patchwork of block grants and tax credits that leave out many low-income families, are difficult to access, and are delivered at tax-filing not when expenses have occurred. For example, the two largest support programs for families—the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) which supplements income for low-income working families, and Child Tax Credit (CTC) which accrues per child and is partially refundable—are delivered once-a-year, which is problematic for families living paycheck to paycheck.

Government support for child care expenses often leaves out low-income families who need support the most. The Child and Dependent Care Tax Credit (CDCTC), a tax credit for child care expenses, is not refundable, meaning that it cannot be claimed by families without an income tax liability, which is most low-income households. The Child Care and Dependent Block Grant (CCDBG), which provides subsidies to low-income households for child care, has been chronically underfunded. As a result, only 1-in-6 eligible children for the program receive child care support. Additionally, the subsidy structure of CCDBG tends to favor center-based care above in-home providers, faith-based providers, and care by friends and relatives, which is not the preferred option of Hispanic families in particular.

Hispanic families tend to have a lower take-up rate of government benefits than other racial groups, irrespective of eligibility. This holds true for SNAP, WIC, Medicaid, the CTC, EITC, and even child care subsidies. According to CLASP, “while 13 percent of all eligible children (ages 0-13, regardless of race/ethnicity) and 21 percent of eligible Black children receive child care assistance through CCDBG, only 8 percent of eligible Hispanic children get help.” While there’s not clarity about why this is, it is likely in part because of language barriers and in part because mixed-status families are often afraid to interact with government agencies, limiting their children’s access to benefits despite their citizen status. While some conservatives may believe that a lower take-up rate is a good thing because it reduces the likelihood of government dependency, it’s a problem if benefits aren’t getting to those they’ve been designed to support.

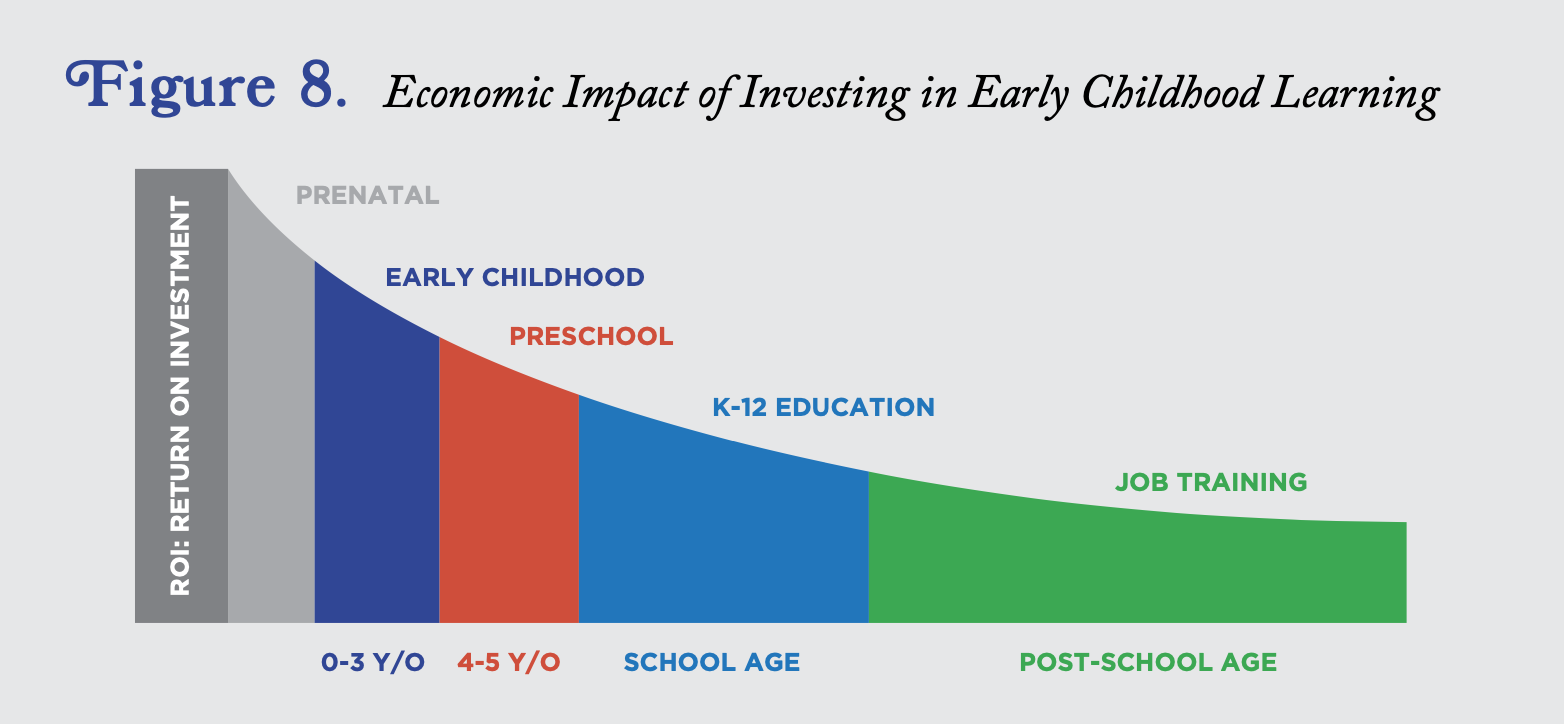

Lack of investment in children makes little sense, as early childhood investment tends to have a much higher return on investment than investments made later in life. This is demonstrated by the “Heckman Equation,” which shows the highest returns on investment for prenatal care, child care, and in-home investments for children ages 0-3, declining in preschool, further in primary school, and even further thereafter with retraining programs and higher education. Heckman’s most recent research found that these gains continued across generations, with improvements in education, employment, crime, school suspensions and health for the children of those who had participated in the Perry Preschool Project. This research suggests that investments in early childhood care and education, properly structured and targeted, could be a critical tool to unlock intergenerational upward mobility and economic opportunity.

SOURCE: HeckmanEquation.org

There is widespread public support for greater investment in families. As a May 2021 Bipartisan Policy Center/Morning Consult poll found, among America’s parents, 88 percent believe expanding government support would be beneficial for parents and children, including 95 percent of liberals, and 79 percent of conservatives. A 2021 American Compass poll found something similar: Across all incomes and regardless of parental status, 60 to 75 percent of Americans say that the government should do more to support families. In all cases, the primary rationales are that “families are falling behind and need help,” or “more assistance to families would improve the lives of children.”

4. PEOPLE ARE HAVING FEWER CHILDREN

Hispanics in the U.S. have a higher fertility rate than other racial or ethnic groups, but it is declining at a more rapid pace.

Today’s birth rate is about 20 percent lower than it was in 2007. This is likely attributable to a wide variety of reasons, such as delayed marriage and an increase in women’s education. Indeed, a decline in fertility is occurring across the developed world, even in countries with significant family-related supports, suggesting a significant cultural shift is occurring. To that point, as argued by AEI’s Scott Winship, it’s not clear that the decline in fertility rates is out of step with people’s desires or preferences. According to his analysis, millennial women have been no less successful than late-boomer women at achieving their desired fertility.

SOURCE: CDC Vital Statistics Reports for 2015, 2016, and 2020.

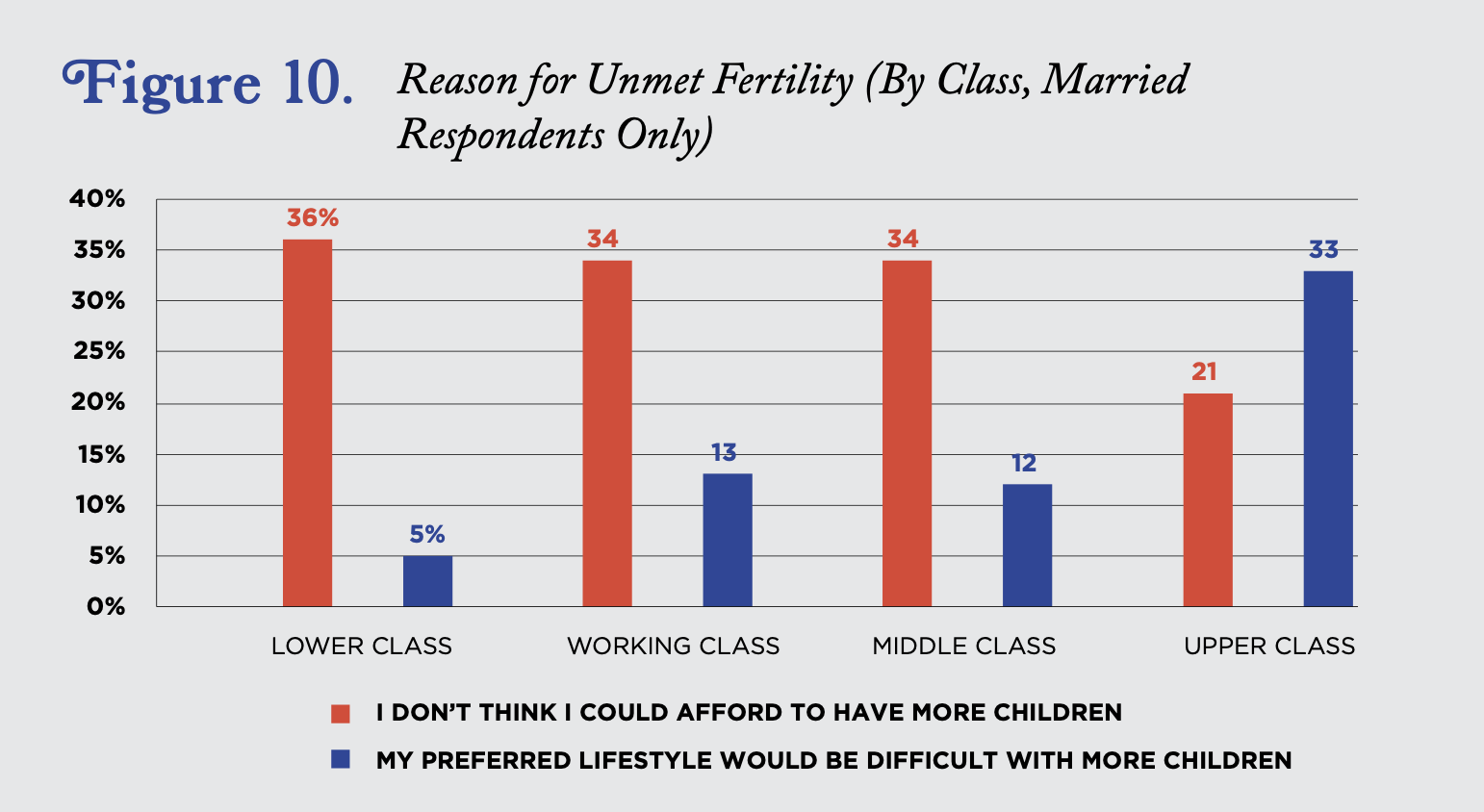

That said, polling evidence suggests that costs may also be a contributing factor for people who are choosing to forgo having (or having more) children. Nearly half of parenting-age Americans say they would ideally have more children than they have had, according to a recent poll. Low- and moderate-income households are at least twice as likely to cite affordability rather than lifestyle or career as the reason they have had fewer children than they want. A New York Times / Morning Consult survey explored this trend further. The poll asked adults who reported having or expecting to have fewer than their ideal number of children the reason for the mismatch. Out of the top eight reasons cited, six were related to finances, including: “Child care is too expensive,” “Worried about the economy,” and “Can’t afford more children.”

Affordability challenges also may impact the ability to sustain a pregnancy. While abortion used to be only loosely related to income, in recent decades abortions increasingly have become concentrated among impoverished women. In the most recent survey of abortion patients conducted by the Guttmacher Institute, nearly half of abortions are performed for women living below the poverty line as of 2014 (up from 30 percent in 1987), and 75 percent were to women considered poor or low-income.79 Women have abortions for complicated and interrelated reasons, but the leading factors from multiple polls are lack of financial security (40 percent) and the likelihood of job or education interruption.

SOURCE: American Compass Home Building Survey (2021).

Hispanics have tended to an elevated fertility rate relative to other racial and ethnic groups in America. Nevertheless, the decline in fertility rates has impacted all demographics, with severe declines among Hispanics. According to the Institute for Family Studies, age-adjusted fertility rates for Hispanics have fallen from 2.85 births per woman in 2008 to 2.1 in 2016, whereas non-Hispanic fertility has declined from 1.95 births per woman to 1.72. This means that half of the “missing kids” over the last decade would have been born to Hispanic mothers.

Again, having fewer children may reflect people’s preferences and increased opportunities more than prohibitive costs. This has been the subject of much debate given that the reason driving reduced fertility impacts the justification and efficacy of a government response. Yet reduced family formation has significant macroeconomic implications. A declining birthrate will decrease the future labor supply and put downward pressure on economic growth. Additionally, with pay-as-you-go social programs such as Social Security and Medicare reliant upon population growth, the decline in family formation could hasten a fiscal crisis.

SOURCE: Institute for Family Studies.

5. PARENTS ARE INCREASINGLY ISOLATED

Hispanics tend to have elevated levels of social capital as measured by marriage, multigenerational households, and church attendance. But they have not been immune to broader trends. In 2016, half of Hispanic children were born to unmarried mothers, up from 34 percent in 1990.

America has the highest rate of single parenthood in the developed world. Nearly one in four American households is headed by a single parent, and two out of five births occurs outside of marriage. Government policy isn’t helping; according to a recent 2022 NBER study, our existing tax and benefit system actively discourages marriage for low-income single mothers by introducing cliffs in benefits if they choose to marry.

Single parenthood directly impacts family affordability. An AEI study by Robert L. Lerman and W. Bradford Wilcox found that growth in median income for families with children would be 44 percent higher today if the 1980s level of married parenthood had persisted. The economic disadvantages of single parenthood are particularly acute for single mothers, 43 percent of whom live at or below the poverty line, compared to 24 percent of single fathers and 10 percent of married parents.

While families are the primary unit of social capital, they are not the only type of relational support. Communities, faith-based organizations, work, and extended families can provide a place of belonging and support. Yet this type of social capital also has frayed in recent decades, as tracked by the Joint Economic Committee’s ( JEC) 2017 report, “What We Do Together.” The weakening of social capital has a direct impact on family affordability. Recent work led by Harvard economist Raj Chetty shows that stable families—combined with school quality, the degree of racial and income segregation, and the strength of social networks—explain more than 76 percent of the variance in upward mobility across various regions. All of these correlates are closely linked to relational and community health more than macroeconomic conditions.

On many metrics, Hispanics have elevated levels of social capital relative to many other racial and ethnic groups. Hispanics have an elevated marriage and cohabitation rate relative to low-income Black and White men and women; have a higher rate of living in multigenerational households than White households (which likely reflects financial constraints but also cultural values); and the highest rate of church attendance behind Black Americans. This could be the reason why Hispanic children have a moderate level of upward mobility, despite challenges such as immigration. Hispanic persons raised in lower-income families reached the 37th percentile, on average, which is only four percentage points below the average rank of low-income White children and eight percentage points above the average for low-income Black children.

Yet Hispanics have not been immune to a thinning of social capital. While marriage rates among foreign-born Hispanics has changed little and is above the national average, it has dropped for domestic-born Hispanics, with the percentage married decreasing from 50 percent in 1990 to 33 percent among men in 2017 and from 51 percent to 36 percent among women. In 2016, half of Hispanic children were born to unmarried mothers, up from 34 percent in 1990, though some of this is due to relatively high rate of cohabitation among Hispanics. And while church membership has been broadly declining over the last decades, Hispanic church membership dropped from 68 percent to 45 percent since 2000, a much bigger decline than for Whites and Blacks.

Parenting is a tight-rope act, and few people have a net beneath them to catch their fall. Children require a tremendous amount of resources—time and financial—but they also require social investment from their household and the community around them.